It’s been 150 years since the Civil War broke out—yet many of its burning issues remain. How does a multiracial society live in harmony? Should the federal government be big or small? Are states’ rights the way of the future, as Tea Party advocates say, or a dangerous anachronism?

“The Civil War made modern America, and some of the arguments still resonate,” says Joseph Bilby of Sea Girt, an expert on military history. He hopes the anniversary will draw attention to New Jersey’s role in that tumultuous conflict.

As a Mid-Atlantic state that extends 40 miles below the Mason-Dixon Line, New Jersey faced difficult choices as the Union fragmented. Its wildly exaggerated reputation as a Southern sympathizer—the New York Times labeled it “the South Carolina of the North”—began with the presidential election of 1860, when Republican candidate Abraham Lincoln performed poorly in the conservative, mostly Democratic state. Ironically, Lincoln ran strongest in South Jersey, where Quaker Abolitionism was strong.

Many predicted economic disaster for New Jersey as Southern states seceded in 1861. Gone were lucrative markets for such Newark goods as carriages and clothes. A former governor audaciously urged New Jersey to “go with the South” for the sake of its business.

Some hoped New Jersey would join a Central United States comprised of border states; others, that it would enter the Confederacy, making Perth Amboy a great port city for the secessionists. Antiwar sentiment was strong, given the risk of invasion by armies of North and South alike. The Camden Democrat foresaw “our gallant little State…crushed and trampled to death.”

As president-elect, Lincoln needed to firm up support in the wavering state, so he spent seven hours in New Jersey on his way to Washington to be inaugurated, making stops from Jersey City to Trenton. Addressing the Legislature, he reminded members of their patriotic duty by recalling the exploits of George Washington in the Battle of Trenton, about which he had read as a boy.

After Fort Sumter was fired upon, initiating the war, Jersey decided its heart lay with the North. It organized regiments and rushed them to defend Washington. “We were as pro-war as any state,” says Civil War historian David Martin of East Windsor. “We more than met every call for troops—40 regiments.”

The first big military parade of the war featured Jerseymen greeted by Lincoln on the White House grounds. Later the president made his first foray into secessionist Virginia to visit them as they dug fortifications, and they saluted him with their shovels.

After the Union army got routed by Confederates in the opening battle of the war, Bull Run, the Jersey Blues (as the state’s troops were familiarly called) fixed bayonets to stop panicked soldiers from running all the way back to Washington.

As predicted, Newark industries suffered from the loss of Southern business, but they soon rebounded thanks to Army orders for guns, uniforms, tents and blankets. Trenton Iron Works retooled to make rifles. The state’s leading railroad, the Camden and Amboy, profited from carrying soldiers southward toward battlefields, and its line was straightened into the route still followed by Amtrak today.

Congress called this “the most traveled and most vital thoroughfare in the Union” but faulted the railroad company for long delays that made journeys “disagreeable, annoying and unsatisfactory.” A proposed U.S. railroad to compete with the Camden and Amboy line typified the big government approach the war heralded. So did the 1862 act of Congress that funded land-grant colleges, of which Rutgers was one.

Fearful of growing federal power, Democrats condemned Lincoln for suspending the writ of habeas corpus and arresting several newspapermen in the state when they spoke against the government—including one who called Honest Abe a “foul-mouthed gorilla.” Most of the state’s 80 newspapers were Unionist, but some were raucously Copperhead, opposed to the war. The Monmouth Democrat wondered why Robert Lincoln, the president’s son, was “sporting away his college vacations at Long Branch” instead of enlisting. Many Jersey Copperheads blamed pro-Lincoln abolitionists for the national bloodletting: “We are cutting each other’s throats for the sake of a few worthless negroes,” one told a Democratic crowd in Trenton. Such anti-black feeling was evident in New Jersey—the last Northern state to outlaw slavery (in 1846)—where a gradual approach to emancipation left more than a dozen elderly house servants still enslaved when the war began.

Angered by the Emancipation Proclamation, some Democratic legislators in Trenton proposed banning ex-slaves from the state and even talked of deporting free blacks to Africa.

New Jersey never created a black regiment. Joel Parker, the state’s wartime governor, said that whites “should not place their reliance on a distinct and inferior race.” So 2,900 African-Americans from New Jersey went to Philadelphia to join U.S. Colored Regiments. One was George Ashby of Crosswicks, who survived the war and eventually became the state’s oldest Civil War veteran. At age 100 he longed to fight in World War II.

In all, one in 10 residents of New Jersey went off to war, about 73,000 men. Many fought bravely, earning the state’s troops a formidable reputation: “Jersey Blue, a name the rebels fear,” one soldier proudly declared. “Of real grit, I think the bulk of Jerseymen have as much as any people anywhere,” said Walt Whitman, a Civil War nurse who later moved to Camden.

But war often seemed more about dreary marching than fighting. “General Burnside called us Jersey muskrats,” a soldier said, “when he seen us in the mud and up to our necks.”

A future Jersey governor, General George McClellan, headed the Peninsula Campaign, the Union Army’s disastrous attempt to seize the Confederate capital of Richmond. Many Jersey Blues were assigned to his corps. At Williamsburg, Virginia, in drenching rain on May 5, 1862, they “fought like tigers,” a reporter said.

Shot in the stomach there, young soldier Daniel Ostrander was laid in a common grave beside his friend. His comrades mailed the contents of his pockets home to his mother in Paterson: $22 in bloodstained bills.

Many officers fell that day at Williamsburg. Major Peter Ryerson, who had formed a regiment of forgemen and foresters in the woods of North Jersey, was struck by a bullet as he tried to rally his fleeing men. He lay dying as the advancing Confederate army thundered over him.

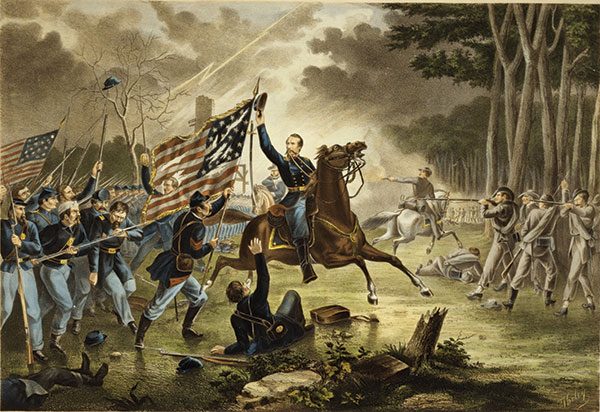

Dashing General Philip Kearny arrived on the Williamsburg battlefield just in time to stop the rout. Few soldiers had more pre-war combat experience: He had fought with the French army in Africa and lost an arm in the Mexican War. On horseback, he held the reins in his teeth as he waved his sword high. After he fell in a storm of bullets in the subsequent Battle of Chantilly, his New Jersey hometown in Hudson County was renamed for him.

Days after Williamsburg came Gaines’ Mill, where hundreds of New Jersey soldiers were slaughtered in a mismanaged attack that an observer called “downright madness.” “It is rather hot in there,” shouted Newark lawyer Colonel Isaac Tucker as his troops entered the woods, “but the Jersey boys will do their duty!” Soon Tucker was dead, his body never recovered. Of 2,800 Jersey Blues who entered the grove that afternoon, only 965 came out at dusk.

In bloody fighting a year later at Chancellorsville, the 7th New Jersey captured five Confederate battle flags. They can be seen today at the State Department in Trenton, where 132 Civil War banners survive as tattered reminders of long-ago campaigns.

Robert E. Lee’s invasion of Pennsylvania in summer 1863 terrified many in the Garden State, who imagined graycoats marching into Trenton. “I think you will not see the foe in New Jersey,” Lincoln reassured the worried governor.

Fifteen New Jersey units were among the forces that turned Lee back at the little Pennsylvania town of Gettysburg, at a terrible price. The 11th Regiment, for example, lost 9 of 13 officers killed or wounded, and 153 of its 275 soldiers.

There were many episodes of heroism. In the Peach Orchard, Captain Judson Clark’s battery of cannon held off a Confederate attack by firing 1,342 rounds, a record for the war. A dozen battlefield monuments today honor Jersey troops at Gettysburg.

Young Cornelia Hancock from Salem County rushed to attend the Gettysburg wounded in a makeshift outdoor hospital, where a wooden table “literally ran blood” and a wagon trundled back and forth disposing of amputated limbs. The stench of corpses “in heaps on every side” was almost unbearable, as were the groans of dying men all lying together, shot through the head and given up as hopeless.

Another compassionate Civil War nurse is memorialized today by a service area on the New Jersey Turnpike: former Bordentown schoolteacher Clara Barton.

Contrary to the fears of many, no battles were ever fought in New Jersey–but strange to say, nearly 3,000 Confederates lie buried in mass graves at Finns Point, Salem County. They died of disease while prisoners at fetid Fort Delaware, which still stands on an island in the river nearby.

By the time the war ended in 1865, 6,000 brave Jerseymen were dead, mourned by families in every town of the state. But with the passing of the generations, New Jersey’s role in the great conflict was virtually forgotten. Its population is 13 times bigger now, many of us descendants of immigrants who arrived long after the war ended.

To inform today’s residents, Bilby, Martin and others are active in the New Jersey Civil War Sesquicentennial Committee, trying to remind a busy modern world about the importance of this bloody, fateful era that nearly split a nation.

W. Barksdale Maynard, author of Woodrow Wilson: Princeton to the Presidency (Yale University Press, 2008), wrote about Wilson in the November 2010 issue.

Click here to read about Civil War reenactors in New Jersey.